UPAA Blog 2022-23 #2 - 9/15/22

Text and photos by University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Photographer Tyler Jones except where noted.

************

Introduction

Virtually every university photographer is familiar with the following: You’re given an assignment to take photographs for an article about some research topic. You coordinate with the researchers, determine a time and location, then you show up and there’s nothing to photograph because the actual research has long been concluded and the data analyzed. So you do your best with an impromptu environmental portrait involving the researchers, their lab, and maybe some photogenic equipment props. You may come away with a decent, or even a great image, but you’re left with the feeling that images made during the research would have been better. In my fifteen years as a photographer for the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) it has almost always been this way.

So I was delighted back in the spring of 2021 when UF horticultural scientists Drs. Rob Ferl and Anna-Lisa Paul requested a meeting with myself, one of our writers and our director of communications in-regard-to coordinating media coverage around some potentially newsworthy research they’d soon be conducting. Drs. Ferl and Paul are two of the leading researchers in the field of space science and its horticultural applications, and their research has always yielded fun and exciting photo assignments, often involving experiments in conjunction with NASA and the former Space Shuttle program.

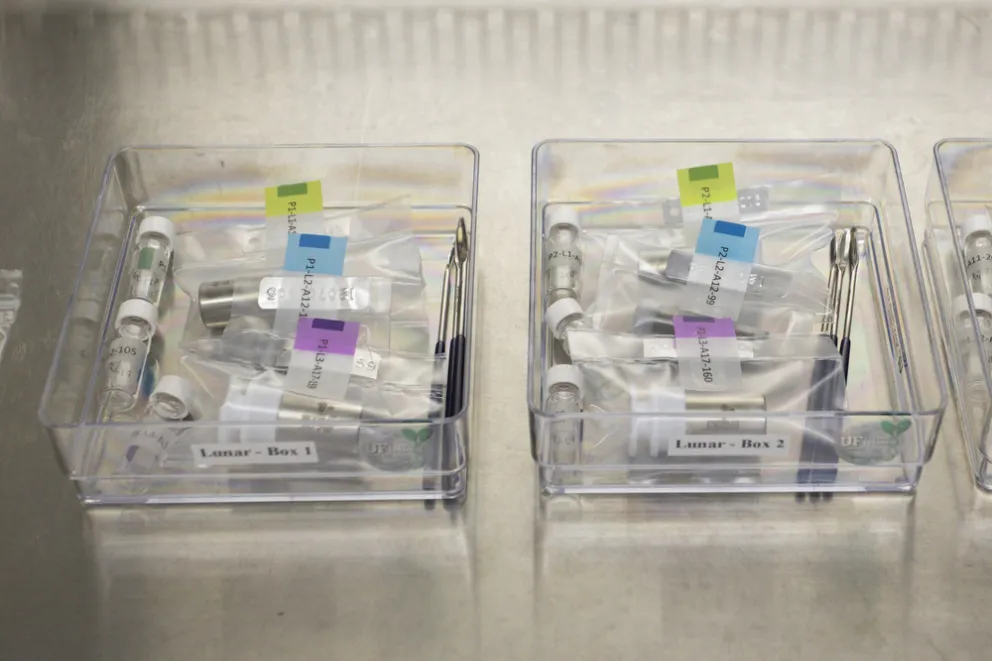

Metal vials containing lunar regolith, unopened since the Apollo program.

My curiosity was piqued in a Horticultural Sciences lab when Dr. Ferl opened a small safe and removed a transparent bag containing some cylindrical stainless-steel containers. The vials were themselves each sealed in smaller bags and all etched with numerical engravings or labels that belied the provenance of their contents. That’s when Dr. Ferl informed us that we were holding some of the lunar soils—which scientists call lunar regolith—collected by American astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, among others, during the historic Apollo 11, 12, and 17 moon missions. As I held history in my hands, a wide grin spread across my face and I knew that whatever they had in mind, it had the potential to be a very big deal.

The Research

After years of formal requests, NASA granted permission to Drs. Ferl and Paul to be the first researchers to try and grow plants in lunar regolith. They’d already succeeded in growing plants in lunar soil replicant--a lab-made soil that mimics the chemical composition of its priceless lunar counterpart--but no one had ever tried seeding the actual soils from the Apollo missions. Such research is vital in achieving a better understanding of the feasibility of growing plants in controlled lunar environments as a key component of establishing sustainable habitats in the next wave of moon exploration that is on the horizon.

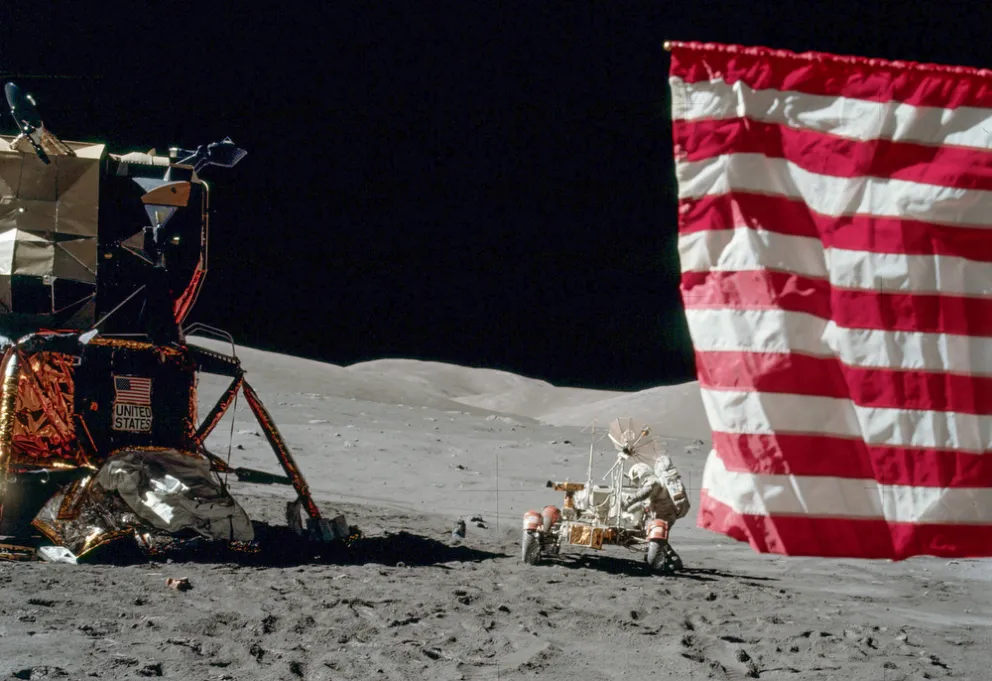

(NASA Photo) Harrison "Jack" Schmitt explores the Taurus-Littrow valley in December 1972 on Apollo 17, the last human-crewed moon mission to date.

My task as a UF/IFAS photographer was to devise and execute a plan of photography and videography that would meet not only the scientific needs of the researchers, but also satisfy the criteria for any future media and press needs. Drs. Ferl and Paul understood from the outset what they were doing was potentially of historic importance and that there could be significant media attention in the wake of the research’s publication. By working ahead of time with us, they could remove the burden of media communications from themselves and focus more closely on the research tasks, while gaining access to professional imagery and established outreach sources through our services.

Anna-Lisa Paul, left, and Rob Ferl, working with the lunar soils in their lab, April 2021.

Sam Murray, a colleague and writer within IFAS Communications Services, would write a story as well as serve as the liaison between the major media outlets and the researchers. After the journal Communications Biology announced exclusive first rights of publication and the media embargo were lifted, the story would be disseminated to the world. The media package Sam would make available and distribute to news outlets would contain a culled down and curated collection of my images and video, all accompanied by accurate descriptive captions, pre-approved by Drs. Ferl and Paul.

We were lucky in this case to get to work with two scientists who value scientific communications and public outreach. Acknowledging that importance and what prompted them to reach out us in the first place, Dr. Ferl stated, “Every experiment has a very human story behind it. Mostly those stories are told to our students and our friends over beers. But tell those stories enough and one develops a sense of human interest in science that can be set aglow. The chance to tell such a story more broadly is the potential that we saw in the lunar plants work. We saw history and exploration colliding in a way that truly suggested that there was a bigger story to tell. So, we took a chance and made the call.”

Photography Logistics

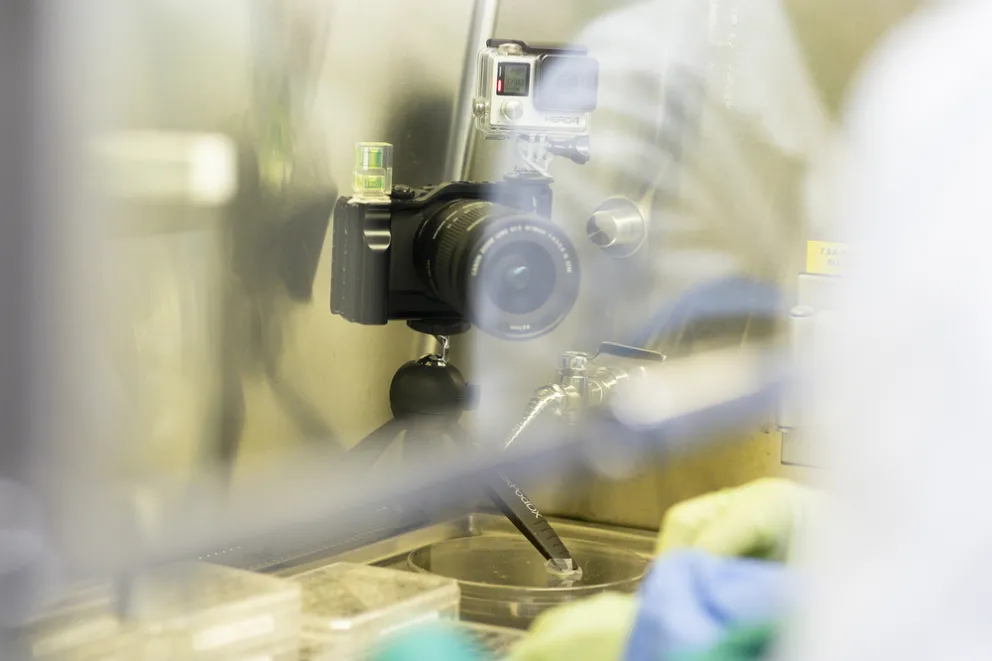

The experiment commenced April 28, 2021 and ran through May, at which time plant specimens were harvested and analyzed for data. I carefully coordinated photography that included the operation of three still cameras and two video cameras, two of which were operated remotely via wi-fi connection between camera and my phone. The remote still camera and a GoPro mounted atop it were in the corner of the lab hood. This was a tight space that would be impossible to get into after the experiment began, so I placed the camera ahead of time and used the remote connectivity feature to take images as needed, while the GoPro recorded video continuously.

Stills and video camera setup in the corner of the lab hood and operated remotely via Wifi connection and a phone in order to get photos and b-roll video of research steps that were conducted beneath the lab hood.

From there, I worked off to the side of the researchers and over their shoulders using two more still cameras, one mounted with a 17-40mm ultra-wide angle to normal lens, and alternating between a fixed 50 and 85mm on the other body for detail shots. I also used one other dedicated video camera with a 24-120mm equivalent lens.

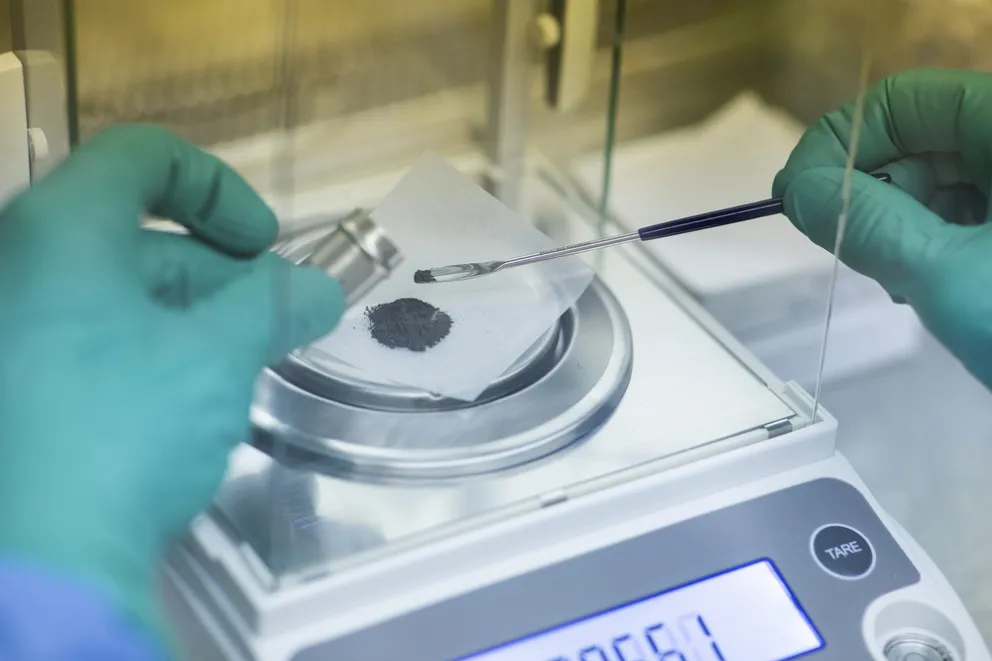

Top: Anna-Lisa Paul concentrates on the delicate process of seeding the arabidopsis in the lunar regolith. Bottom: Rob Ferl weighs lunar soil. The soil samples had been sealed in vials since the time of the Apollo 11, 12 and 17 missions to the Moon.

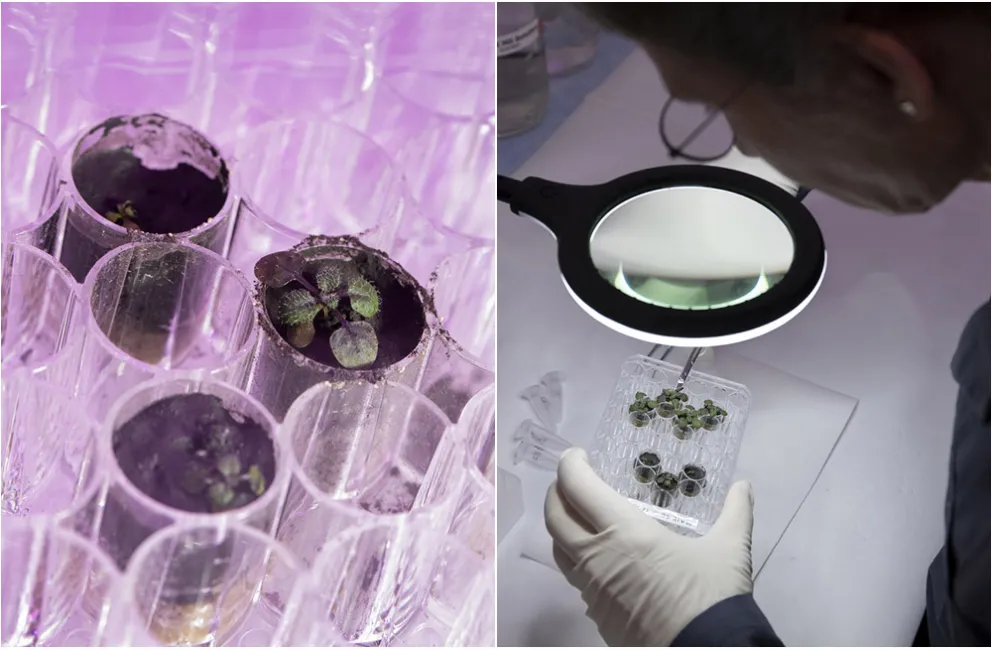

In the next phase of the experiment, the specimens were moved to a growth chamber where artificial LED lights and temperature controls would provide a controlled habitat. There I would photograph the sprouting plants every few days according to the researchers’ needs. One need was to have a series of growth comparison photos and for that I used a tripod with a horizontal extension arm and still camera mounted to the end of it, allowing me to replicate a series of top-down images of the plates and plants growing within them. These images needed to all match one another throughout the growth cycle and would be utilized as visual data depicting growth progression.

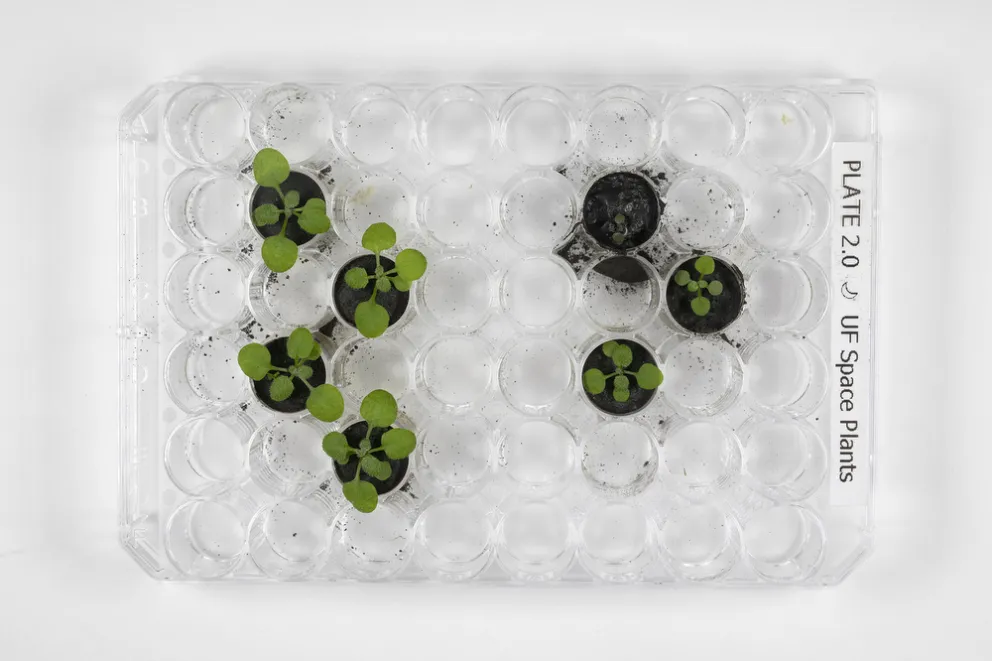

One of the top down photos comparing daily arabidopsis growth between the simulant lunar soils (left) and the Apollo 11, 12, and 17 soils (right). By day 16, there were clear physical differences between plants grown in the lunar simulant, compared with those grown in the lunar soil.

While each plate was being photographed for comparison purposes, I used a second camera outfitted with a 90mm equivalent macro lens and an external Profoto A1 flash to take more artistic images of the first sprouts emerging from the lunar regolith. These images were aimed at any possible journal or magazine covers and could stand on their own as the beauty shots representing the research if need be. These images were my favorites and depict the first plants in human history to ever be grown in non-Earth soils.

An Arabidopsis plant grown in lunar soil for about two weeks.

As the researchers expected, plants did successfully grow in the lunar soils. There were differences between those in the replicant soil and those in the lunar soil, as well as some unexpected obstacles to work around, such as the fact that lunar soils are extremely hydrophobic, meaning that they do not absorb water as effectively as replicant soils do.

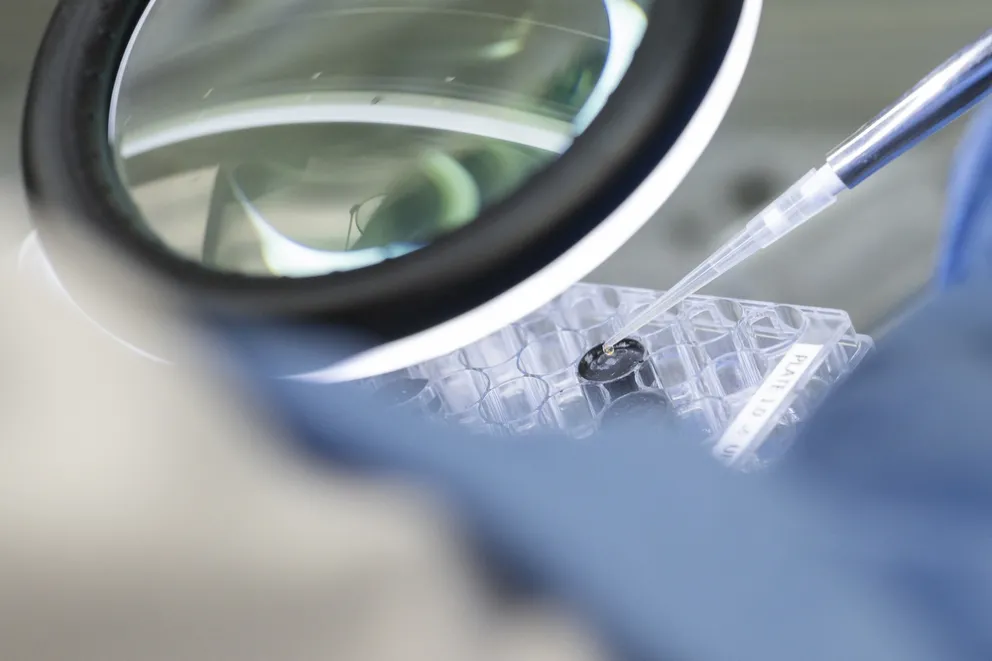

Anna-Lisa Paul attempts to seed one of the Apollo 11 soil wells with the arabidopsis. Arabidopsis seeds can be seen in the water droplet at the tip of the pipette.

Plants did grow in soils collected from all three Apollo missions but showed signs of stress such as reddish-purple pigmentation. My photography and videography plan worked with minimal complications, and I was extremely pleased with the resulting imagery. In my mind it was further evidence that working ahead of a research story and planning its media release can be a highly effective strategy in not only getting better quality images, but in the story reaching a wider audience.

Top: All lunar and simulant soils seeded, Rob Ferl (far left), and Anna-Lisa Paul (second from right), carry the finished plates from their horticultural sciences lab to the growth chamber where the remainder of the experiment would be conducted. Bottom left: Twenty-day-old Arabidopsis plants growing in lunar soil. Bottom right: Anna-Lisa Paul does the delicate work of harvesting plants for genetic analysis.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned

Mass media dissemination for this story was extraordinarily successful. Our potential reach (defined as the approximate number of article views we appeared in) across all media outlets globally was 5.39 billion views. Our images and video ran on virtually every notable news and media outlet nationally and internationally. Reuters, the Associated Press, TIME, CNN, Wired, Scientific American, Nature, NPR and the BBC are just several of the thousands of notable outlets that featured our content. The story was also a high performer across social media, with NASA’s promotion helping it gain an estimated 267 million views. It is currently the University of Florida’s top performing story of all time.

(NASA photo) The story took off like...well... The launch of Apollo 17 in December 1972, the only night launch of the Apollo program, and one of the missions that provided the UF/IFAS samples.

This unprecedented success is partly due to long-term relationship building, specifically, the type of relationship building that we, as image makers, have control over. Researchers may or may not be familiar with their communications director, and while they may have had dozens of phone calls and email exchanges with a writer, it’s often the photographers they interact with the most. For years, I argued the case that our task of making exceptional research imagery is difficult because we don’t get the assignment until principal research has been concluded. I began asking researchers to coordinate with us ahead of time if they felt they had something newsworthy on the horizon and to allow us to get visuals while research is being conducted.

Just a small sample of clips from external media: Washington Post, Wired, Smithsonian and Astronomy.

Dsr. Ferl and Paul understood the importance of such relationships. Dr. Ferl stated, “We felt comfortable with you as the photographer because we could draw upon that trust and respect that was developed over time. It was experience and trust that let us put our story in your hands." Researchers will listen if you have developed a rapport with them and have produced quality imagery that has met their needs in advancing their research and publications.

Rob Ferl, left, and Anna-Lisa Paul looking at the plates filled part with lunar soil and part with control soils, now under LED growing lights. At the time, the scientists did not know if the seeds would even germinate in lunar soil.

We need to view our roles not strictly as photographers or videographers, but as communications ambassadors. When science is increasingly maligned in the public eye, there is a greater need for research stories to resonate and inspire. Building these relationships of trust reassures our campus researchers that their science will be conveyed accurately and in a meaningful way by us and our talented communications colleagues. In this way we can play a small but not insignificant role in advancing science and the public good.

************

"I had a joke about a mission to the moon but it was so bad I couldn't publish it...I Apollo-gize." Thanks for reading the blog. Would you like to see more, different, better articles? Send articles, suggestions and jokes to editor Matt Cashore, mcashore@nd.edu. And of course, follow UPAA on Instagram!