UPAA Blog 2020-21 #8 - 11/5/20 (text and photo above by Matt Cashore)

Matt Cashore is editor of the UPAA blog. He's a part 107-licensed drone pilot, and a commercial-licensed fixed wing pilot with over 1700 hours, so he's taken several FAA exams and checkrides, and is allowed to say words like "Roger," "Niner" and "Vector" on the radio. And yes, he is talking about himself in third person.

The FAA - not exactly known for being on the pointy end of the innovation stick - has been astonishingly quick to introduce drone-specific laws, programs and procedures. For example: As recently as 2014, the only path to a drone pilot license was to have a full-on private pilot certificate. Only two years later the Part 107 license was an option. LAANC automated flight planning/approval was another nimble-by-FAA standards response to the needs of drone pilots flying near busier airports.

But, quicker than you can say “hold my beer,” people still find ways to do dumb things with drones. Mid-air collision is near the top of the “what if?” list, and despite clear language in the regs (Part 107 5.12: “A remote PIC has a responsibility to operate the small UA so it remains clear of and yields to all other aircraft.”) there are verified reports of drones colliding with helicopters, fixed-wing airplanes and even hot air balloons. Recently, a widely-shared video showed a drone pilot coming recklessly close to The Blue Angels. Though none of these instances resulted in injury or anything more than minor damage, there was the potential for a significant incident, and even close calls damage the credibility and public perception of all drone pilots.

(screenshot from YouTube) This...was not a good idea. The drone would have been invisible to the formation lead pilot. A collision at 200+ miles per hour would have at least caused significant damage, or worse.

In the 'drone vs balloon' collision mentioned above, the drone was intentionally flown near another aircraft (which is not, strictly speaking, illegal, believe it or not!) but in the other two examples, the drone pilot may not have been aware another aircraft was approaching. Helicopters in particular often fly lower and not on predictable approach and departure paths. Perhaps in those cases a "heads up!" to the drone pilot could have avoided the collision.

(photos by Matt Cashore) Private and scheduled air traffic passes over the Main Building at Notre Dame regularly at known and consistent paths and altitudes. Drones can safely fly at or below pre-determined altitudes thanks to the LAANC flight plan system and the traffic passing above is not a factor. But every now and again we get un-predictable air traffic...

Responsible drone pilots would welcome more flexibility in current regs such as line of sight requirements, flying at night, or near people. Public displays of boneheadedness aren’t going to help loosen the rules, however. The FAA does not have the resources necessary to enforce common sense. But industry does!

DJI manufactures 75% of all drones sold in the U.S., and they are increasingly playing the role of “digital nanny,” electronically forcing common sense on those who - intentionally or not - lack it. For example: Geo-fencing limits altitude or prevents takeoffs altogether in certain airspace, and in 2020 DJI began equipping all new drone models over 250 grams with the ability to detect and locate manned aircraft. DJI calls this AirSense. The Mavic Air 2 is the first consumer drone to be equipped with AirSense.

(photo by Matt Yeoman) The Mavic Air 2, the first consumer-level DJI drone with AirSense.

How does AirSense work? It takes advantage of a new technology in manned aircraft called ADS-B. Beginning in 2020, all manned aircraft operating around medium sized airports or larger must emit a signal that enhances their visibility on radar to air traffic control as well as to other aircraft nearby. The general idea behind it was to help more airplanes safely operate closer to each other and ease air traffic bottlenecks around the nation’s busiest airports.

ADS-B brings some serious situational awareness, showing at a glance the location, direction, altitude and speed of nearby aircraft. This is a screenshot from ForeFlight, a common app among both private and airline pilots. The receiving aircraft is in blue on the upper right of the image, flying southeast to position for a practice instrument approach into the Warsaw, IN airport. N75649 (upper left corner) is 1200 feet below ("-12"), flying straight-and-level, and heading generally in the opposite direction. The "vector line" indicates a low speed. N525J is 6300 feet above (+63) and descending (down arrow), but also going in the opposite direction, and pretty quickly, too, shown by the long vector line. PRD715 has just taken off from Warsaw, is 1300 feet below and climbing (up arrow). At the moment it's headed away from the airport and at a pretty good speed, so it shouldn't be a factor but keep an eye on it in case it turns.

Detecting airborne traffic once took airliner-level equipment but thanks to ADS-B, real time traffic info can be picked up by inexpensive devices such as iPhones and iPads, so it was an easy feature to add into a drone app.

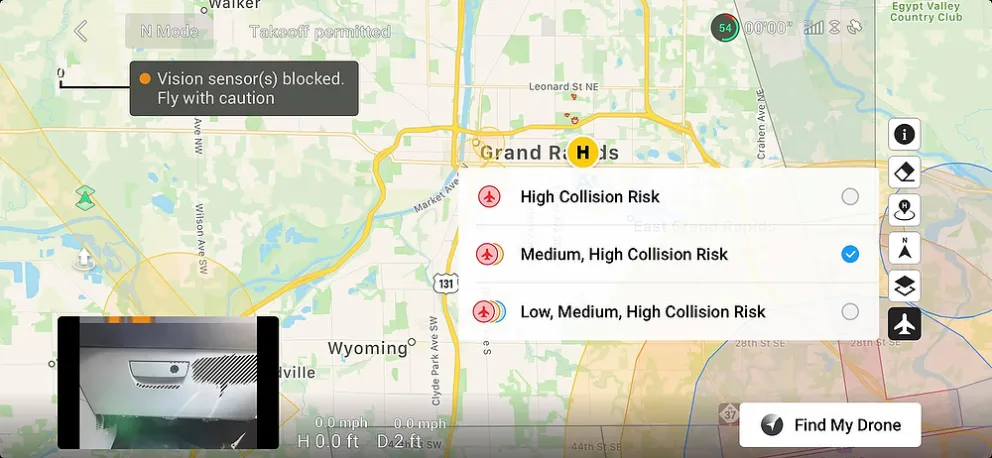

At the time this was written, AirSense only offers 3 sensitivity settings. There is no info in the interface or on DJI's website as to how close an aircraft has to be to trigger each level of warning. Matt Yeoman, who kindly made this screenshot, guesses 1/2-mile to 1 mile on the "medium" setting. Most light aircraft can close that distance in about 30 seconds.

AirSense does:

-Show the real-time location and movement of nearby manned aircraft but not altitude, even though ADS-B transmits that info. It’s an ‘assist’ with visually acquiring the aircraft and then it’s up to the drone pilot to take whatever action might be necessary to yield to that aircraft.

AirSense does not:

-Detect other drones

-Make your drone detectable by airplanes

-Automatically take any action; it’s still the drone pilot’s responsibility to land or move out of the way.

And it’s worth noting that not all manned aircraft are required to have ADS-B equipment. A farmer flying a Piper Cub off a grass strip probably doesn’t have it, but if you’re within 20 or so miles of an airport with airline service, ADS-B is most likely mandatory.

(photos by Matt Cashore) Top: Not all air traffic is airline traffic. Grass runways are in more places than people might think, and a vintage airplane like a Piper Cub is not even required to have a radio, much less ADS-B. Bottom: TV news helicopters, crop dusters and/or medical helicopters might be in unpredictable places and operating at drone altitudes. These aircraft would likely have ADS-B.

Bottom line--knuckleheads are gonna knucklehead. The "digital nanny" can be defeated in any number of ways, and AirSense can be turned off or ignored. AirSense won't force common sense on those who don't want it but it will definitely help those who do. AirSense is a tool which will help with situational awareness and safety and perhaps give a bit of a credibility and PR boost to drone flying generally. It may be a first step in loosening certain regulations like ‘line of sight’ restrictions.

IN USE:

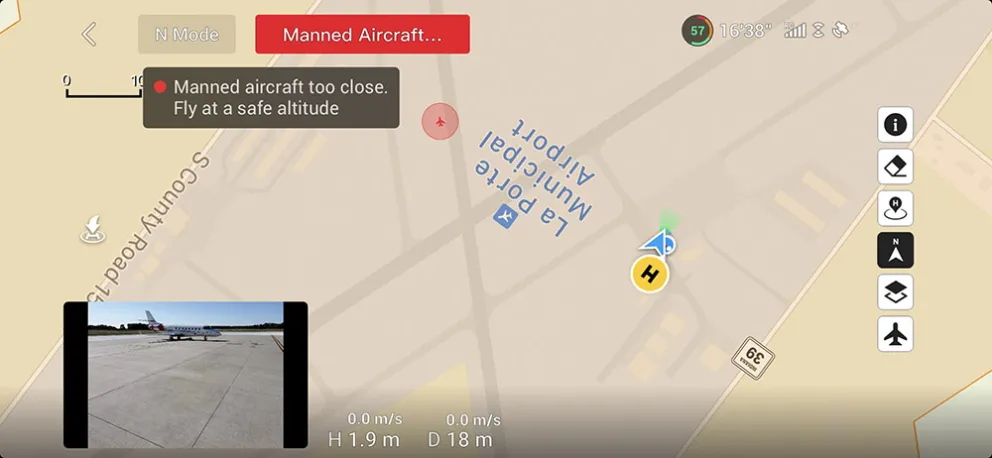

A test of AirSense was arranged at the LaPorte, IN airport. All pilots involved were properly briefed and all necessary permissions were obtained.

(photo by Matt Cashore) "Hey Ridley...got any Beemans?" AirSense is by default turned off and must be activated in the app.

AirSense detects the test airplane approaching. At this point the airplane is approximately 1 mile away from the drone operator (yellow "H") and AirSense signals a "medium" collision risk. The airplane icon isn't that conspicuous on the map and there is no altitude or speed noted. There's room for improvement there but it's still nice to get the "heads up" that an airplane is approaching and it does indicate where to look.

Above: The test airplane is within the airport boundary triggering the "high collision risk" alert. The drone will not take any action automatically. By law the airplane has priority and it's up to the drone pilot to do what's necessary to avoid conflict. Below: (photo by Matt Cashore) The test airplane is visible in the background behind the Mavic Air 2.

DOGFIGHT:

Having both a Mavic Pro 2 and a Mavic Air 2 in the same place for this article, a side-by-side comparison would be expected and the UPAA blog delivers! Buckle up for the fiercest fight in the sky this side of Maverick and Iceman...Okay, not really, this isn't a comprehensive comparison but simply an un-scientific test of the still photo capability of each.

(photo by Matt Cashore) The Mavic Pro 2, left, was released in 2018. It has a 20MP 1" sensor and Hasselblad-branded optics. The Mavic Air 2 was released in April 2020. It has a 48MP smartphone-sized sensor and standard DJI optics. Which will deliver better photos? The drone with the physically larger sensor or the drone with more than 2x the megapixels? Previous UPAA blog articles have demonstrated the benefits of larger sensors, would that hold up in this comparison?

(photo on left by Matt Cashore, photo on right by Ryan Juszkiewicz) On the left, Mavic Pro 2, on the right, Mavic Air 2. Both drone cameras were set to full auto. The Mavic Air 2 has punchier colors and a warmer, more appealing tone generally.

Zoom in--way in!--to check fine detail and the benefits of a larger sensor and better lens are somewhat apparent...but only at pixel-peeping levels of nit-pickiness. The Mavic Air 2, on the right, shows some signs of chromatic aberration around sharp edges and lines vs. the Hasselblad camera of the Mavic Pro 2 on the left. Would you really notice this, even in a large print? Probably not.

And the Top Gun Trophy goes to...? Goose. Hard to say there's a clear winner, but read on:

The Mavic Pro 2 does have minor advantages in terms of still photo quality, but that would go unnoticed in most situations. Video capability wasn't part of this test so who knows if there is a clear winner there...(?) However, the extra safety features, more user-friendly app, smaller form factor and much smaller price (Mavic Air 2 is half the price of the Mavic Pro 2) combine to make the Mavic Air 2 the best overall drone value at the moment.

_________________________________________________________________

"One of the life saving men snapped the camera for us, taking a picture just as the machine had reached the end of the track and had risen to a height of about two feet." - Orville Wright

Thanks for reading the blog. Stories, suggestions and feedback welcome any time. Email mcashore@nd.edu. Follow UPAA on Instagram.